A Life's Story

August 01, 2020

How the Sausage King got made

Master butcher Walter Klopick was a piece of the North End's connective tissue

By: Ben Waldman

Some artists paint murals. Some create sculptures. Walter Klopick made garlic sausage.

It was 1972, and Klopick had just started his own grocery store, Taurus Meats, on McPhillips Street between Pritchard and Manitoba. The business was struggling, and Klopick, who lived with his wife, Olga, and their children in a small suite behind the store, needed a boost.

His mother slipped him a recipe.

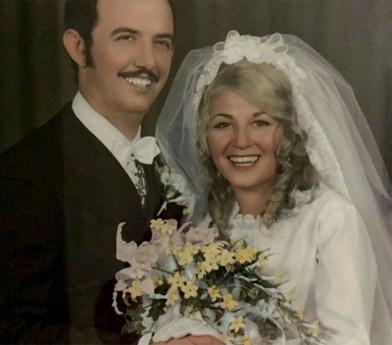

She was a reserved woman, but she saw an opportunity to help her son make good on his latest business gambit. After buying a house in Margaret Park as newlyweds in 1967, Klopick convinced Olga to sell it so they could buy the shop. It was a huge risk for the couple, who were in their 20s with two small children, but Walter believed in himself.

Confidence can only get one so far. Sometimes, you need an ace up your sleeve.

On the recipe card were the handwritten instructions for making her father’s kobassa — a garlic pork sirloin sausage with Ukrainian and Polish origins.

"She said, almost gently, ‘Here, make this,’" recalled Olga. So Klopick got to work, mixing the meat and spices in a small enamel tub in the Taurus backhouse kitchen and putting it through a meat grinder his father, a machinist, had rigged up again and again, tasting and perfecting.

He tinkered with the salt level, and for two years fine-tuned the recipe before finally figuring out the optimal combination. The artist had produced his masterpiece — a peppery, garlicky concoction that would link him to Winnipeg long after his death in January at the age of 74.

"Walter always wanted to be self-employed, and he was bound and determined to make only the best products," said Olga Klopick, who fell for her husband at a St. John’s High School dance. "He believed in what he was doing, and he was always going to do it in the North End."

SUPPLIED

Klopick — the King of Kobassa — started Tenderloin Meat & Sausage in 1985.

After selling Taurus, the Klopicks purchased an old kosher butcher shop at the corner of Main Street and Lansdowne Avenue in 1985. They initially hoped to find a butcher to lease it, but eventually, it was decided that Klopick would start his own shop there: Tenderloin Meat & Sausage.

It was there that Klopick would be dubbed — or dub himself — the King of Kobassa, the pork sausage rocketed to success in an ex-kosher butcher shop. But there was more to the man than what he made.

Klopick was born in Winnipeg in April 1945 — hence the name Taurus Meats — and grew up with his parents and his brother, Frank, in a house on Barber Street. His father was a machinist for the railway, and his mother was a housewife. As the family got more successful, they started taking trips to Nutimik Lake, sparking his life-long love of relaxing at the cottage.

If not behind the counter, he was always dressed to the nines, his shoes polished, his moustache neat, his pants properly creased, his sports jacket hanging coolly on his shoulders, and his hair be just right. "I called him Imelda (after Imelda Marcos) because he had so many shoes," Olga laughs. He also loved his Pontiac GTO, and was a skilled carpenter.

He was dedicated to the St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church and the Knights of Columbus, but his dedication to family and business above all. He poured every bit of himself into the business with the hopes that it’d become a true family business, and that his and Olga’s sons would one day learn the ropes.

SUPPLIED

Walter Klopick

“King of Kobassa”

- founder of Tenderloin Meat & Sausage

Both Chris and Zenon Klopick, who died in 2016, did just that, becoming part owners in 2005. But pretty much from the time Tenderloin opened, the boys were put to work, Chris said.

But it took until the early 2000s for Walter to start teaching them the recipes. "He didn’t want just anyone to know," Chris said. "Everything was weighed out to the gram, and he liked to be over your shoulders when he was training you. Back then, I’d say, ‘I can handle this,’ and we got into a few arguments.

"He’d say, ‘I’ll be right over your shoulders until the day I die, so long as you’re in this business. True to his word, he was."

Chris originally thought his father was being too picky and too much of a perfectionist: he had every ingredient and spice lined up in order on the shelf, and Zenon would sometimes switch one to play a small prank on his old man. But it soon became apparent that everything Walter did at the shop, no matter how particular, was done for a reason.

"Even today, we make the spices the same way I was taught," said Chris. "Nothing’s changed from the way he taught me."

SUPPLIED

Walter Klopick

“King of Kobassa”

- founder of Tenderloin Meat & Sausage

Klopick was a true traditionalist, and that influenced more than the recipes Tenderloin made. When the idea of expansion or relocation was floated, Zenon and Chris both considered the southwest part of the city. But Walter wouldn’t hear it.

"These people helped us start, and they’re going be the ones to keep us in business for the rest of our lives," Chris remembers his dad saying. The shop didn’t move far: a new 12,000-square-foot spot opened on the opposite corner of Main and Lansdowne in 2017.

The grand opening barbecue saw Walter, who’d been dealing with health problems including cancer in recent years, at his true best, schmoozing the locals and starting up conversations with total strangers as though they were lifelong friends. "He really was larger than life to all of us," says Olga. "He had such a presence."

That presence still lingers, in his recipes and in the Luxton neighbourhood, where for 35 years Klopick plied his trade, told his stories, handed out lollipops to children, and beamed with pride.

Klopick’s mother was right: the garlic sausage was a success, accounting for nearly half of Tenderloin’s revenue, with 600 pounds of kobassa being stuffed on average each day.

SUPPLIED

Walter Klopick

“King of Kobassa”

- founder of Tenderloin Meat & Sausage

Along with a dedicated staff, Chris continues to work at the shop and build his father’s vision.

He has his old recipe book up in the office, though it’s written in a code of Walter’s creation, and he sometimes stores it in a safe if he goes out of town. And every morning as he walks through the shop’s doors, Chris thinks of his father.

"A few weeks back, I tried a few new recipes, and I couldn’t figure out why something wasn’t working. I can’t ask him anymore, so I think, ‘What would he ask me?’ He’d say, what did you use, which meat, which spices, is it cured or not," he said. "And I’d sit there frustrated: of course I knew the answer. But he’d say, ‘Let’s slow things down, break things apart, and figure out what happened."

"Every morning, I can hear those things. I can almost see him, still over my shoulder," Chris said.

"It took a number of years, but I am now seeing what he saw, feeling what he felt. All those years of him being tough on my brother and I, it’s led to all this," he said. "I can see it going on forever."

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

A Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View MoreA Life's Story

December 13, 2025

Born to be wildly enthusiastic

Full-hearted family man, actor, photographer, teacher, motorcyclist lived life at full throttle

View MoreA Life's Story

December 06, 2025

A winning hand

Devoted matriarch made most of cards she was dealt

View More