A Life's Story

June 13, 2020

Prodigy's promise ful-Philled

Winnipeg-born musician Lorne Munroe, who left home at the age of 12 to study overseas, spent 32 years as principal cellist for the New York Philharmonic, where he was 'an unfailingly kind and unflappable gentleman'

By: Jen Zoratti

Before Lorne Munroe was Lorne Munroe, principal cellist for the New York Philharmonic — a chair he held for 32 years and more than 150 solos — he was a young cello prodigy in Winnipeg.

Sheila Rodgers never had the thrill of seeing her big brother, who left home at the tender age of 12 to pursue his dreams, perform in New York City with the Phil. But when she was a little girl, she got something of a private concert through the walls at night.

"I remember going to sleep, listening to him practise," says Rodgers, 91, who now lives in Lethbridge. "That was a warm, fuzzy feeling, dozing off and listening to him play."

Munroe died May 4 at the age of 95. He knew the only way to Carnegie Hall — or, in his case, Lincoln Center — was to practise, practise, practise. (Though, he’d perform at Carnegie, too.)

Born in Winnipeg on Nov. 24, 1924, Munroe began his cello studies at the age of three on a modified violin with a leg attached, under the instruction of the distinguished Hungarian cellist Dezsö Mahalek. Music was big in the Munroe family; his parents, Zoe and W.R. Munroe, both studied and played music. Zoe taught Sheila and her youngest, Gilbert, how to play the piano. W.R., meanwhile, loved the violin.

Lorne was "discovered" in 1935 when he competed in the Winnipeg Music Festival, then the Manitoba Music Festival. At 10, his prodigious talent was already asserting itself. He was best in the senior cello class, and was in serious contention for the Aikins Memorial Trophy, which is still awarded for the most outstanding performance in a competition of diploma-level instrumentalists.

"That’s when the adjudicator called him a genius," Rodgers says.

Jan Robert Munroe photo

Cellist Lorne Munroe had a distinguished career and was the first Canadian to win the prestigious Naumburg Award in 1949.

But, because of his young age, the adjudicator, British composer Arthur Benjamin, awarded the coveted prize to a teenage pianist "who wouldn’t have the chance to try again, probably, as Lorne, he assumed, would," Rodgers recalls. "But Lorne never went in the festival again, so he never got the Aikins."

Lorne’s little sister and brother, however, are both Aikins trophy winners: Sheila won it in 1946, Gilbert in 1949. "We both had the Aikins trophy and Lorne didn’t, which is funny because he was so outstanding," she says with a laugh.

As it turns out, Benjamin had other plans for Lorne. Two years later, Lorne, just shy of 13, was getting ready to further his studies an ocean away at the Royal College of Music in London, sponsored by the composer. He’d gone as far as he could in Winnipeg; his much-admired Mr. Mahalek was moving to Vancouver.

"Lorne did not have a teacher anywhere near the quality of Mr. Mahalek," Rodgers says.

Munroe’s parents, meanwhile, weren’t exactly thrilled about the idea of their eldest moving so far away. "They weren’t enthusiastic about it, but people were saying, ‘Oh, you can’t stand in his way,’" Rodgers recalls. "So, they let him go."

After his time in London, Munroe studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia under Gregor Piatigorsky and Orlando Cole, before returning to Europe under much different circumstances: as a member of the U.S. Army, serving in the Second World War.

"He was barely 19," Rodgers says. "I think my mother wouldn’t have minded if he was able to join Glenn Miller’s (Army Airforces) band which was starting up then, but he was too late applying, so he joined the infantry."

Munroe was wounded in the leg during the Battle of Bologna. "He told me once when we were talking about it over the phone that he was lying there on the battlefield, thanking God that his hands were all right," Rodgers recalls.

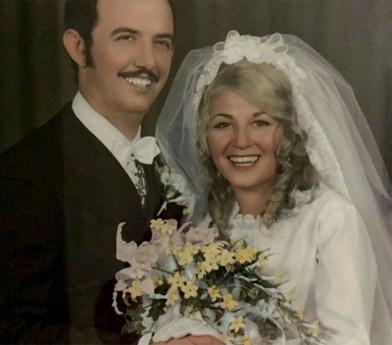

SUPPLIED

Munroe competed in the Manitoba Music Festival at age 10, where his prodigious talent was already asserting itself.

He was sent to Paris to recuperate, which is where he met the woman who would be his wife and best friend of more than 60 years: a violist from Portland, Ore., named Janée Gilbert. She was a member of the USO, and performed for the troops with an all-women orchestra. The couple was married in Paris in 1945.

The newlyweds made their home outside of Philadelphia, and Munroe finished his studies at Curtis. Their family was growing; he and Janée would go on to have 10 sons and one daughter. "Every Christmas we’d get a picture. One, then two, then three, then there was a set of twins," Rodgers says, laughing.

At the same time, Munroe’s career was taking off. He won the prestigious Naumburg Award in 1949, the first Canadian to do so, and made his formal New York recital debut that year, performing works by Haydn, Weber, Dvorak, and Faure. The early 1950s took him across the Midwest, first as a member of the Cleveland Orchestra, then as principal cellist for Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. After a season in Minnesota, the Philadelphia Orchestra hired him in 1951. He was principal cellist there for 13 years.

And then, in 1964, Leonard Bernstein, the famed music director at the New York Philharmonic, tapped Munroe to be his first cellist. Munroe spent 32 seasons there, and was featured as a soloist more than 150 times. In a post on its website last month, the New York Philharmonic remembered him as "an unfailingly kind and unflappable gentleman" who "passed along his legacy, learned from teachers including Piatigorsky, to his students at the Philadelphia University for the Arts and The Juilliard School."

Indeed, between rehearsing, performing and teaching, he clocked many miles on the Amtrak, returning to his Philly suburb to be with his family on weekends. Munroe wasn’t just a career man. He loved spending time with his family, as well as on his non-musical hobbies of photography and fishing, the latter a holdover from his childhood summers at Lake Manitoba.

Rodgers recalls visiting him at his family’s cabin in Maine. "Lorne would sometimes just like to go fishing alone, quietly. He’d get up really early and tiptoe out of the cottage and head down to the dock, and look around — and there would be about four or five boys following him because they knew where he was going," she says with a laugh. "They sleepily followed him and wanted to do it, too."

As a sleepy child herself listening to him play in the next room all those years ago, Rodgers doesn’t recall admiring her accomplished older brother. "He was just my brother," she says. "But more as a teenager, I was knowing what he was doing and what he’d achieved — and especially as an adult, I have admired his work over the years."

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

A Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View MoreA Life's Story

December 13, 2025

Born to be wildly enthusiastic

Full-hearted family man, actor, photographer, teacher, motorcyclist lived life at full throttle

View MoreA Life's Story

December 06, 2025

A winning hand

Devoted matriarch made most of cards she was dealt

View More