A Life's Story

June 24, 2022

'It was about doing work that you believed in'

Robert Archambeau, 89, leaves legacy as one of North Americaâs foremost ceramic artists

By: Erik Pindera

He was the son of glassblowers and bricklayers, a bodybuilding beatnik, and the first Manitoban to win the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

After a life of acclaimed artistry, Robert Archambeau died April 25 at Victoria General Hospital in Winnipeg, at age 89.

His heart had been failing for several years, son Robert Archambeau says, and it was simply no longer strong enough to do its job.

Archambeau leaves behind a legacy as one of North America’s foremost ceramic artists. He specialized in wood-fired clay pots inspired by traditional pottery in Japan, South Korea and China, as well as the landscapes around his studio in Bissett, but to hear his son tell it, that legacy wouldn’t matter much to him.

“He was absolutely unconcerned with the art world and its reception of the kind of work he would do. He was unconcerned with reputation — he won the Governor General’s Award eventually (in 2003), but none of that stuff mattered to him,” Robert says.

“I don’t imagine that there’ll suddenly be a huge revival of interest in Japanese-oriented ceramic art. But I think people who know what they’re looking at will always recognize what he accomplished. I think he would be appreciative of that… he gave a lot of work to people he could tell were really appreciative.”

Archambeau would insist people use the functional art — bowls and teapots — as things they could live with and use. “He didn’t want them all behind glass in a museum.”

Archambeau was born April 18, 1933, in in Toledo, Ohio, into a family of blue-collar craftsman. Although he broke with his background, that tradition inspired his work.

“I think one reason he got into ceramics was you worked with tools and you worked with kilns and you got dusty and muddy,” Roberts says.

“Conceptual art, where it’s all the idea and the execution is unimportant, that was never something that really appealed to him. And I think that sort of work ethic of going into the studio and putting in an eight- or 10- or 12-hour effort, I think that was very appealing to him.”

Archambeau ran off to join the United States Marine Corps at 16, prior to the Korean War, spending his time in the service in the Mediterranean, North Africa and Turkey. During his service, he got into bodybuilding and wrestling.

“What he liked about bodybuilding, his words: ‘You couldn’t bulls—t it.’ Either you could lift the weight or you couldn’t lift the weight, you got out of it what you put into it. And there was no publicizing your way or networking your way into success in weightlifting,” his son says.

From there, Archambeau spent time as a “kind of beatnik” in Mexico and in California, where he lived on Venice Beach.

“And I mean on the beach, and sometimes sleeping in a bar that a friend of his owned — this was when he was a bodybuilder. And I think some of the people he met there, and that was a sort of really ’50s bohemian environment, I think it’s through that that he got into art making,” Roberts says.

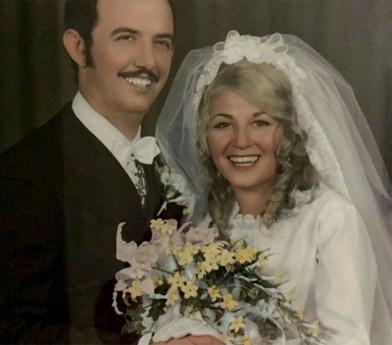

Archambeau went back to Ohio to study for his bachelor of fine arts at Bowling Green State University, where he met his wife Meri. He later obtained his masters from Alfred University in New York (which his son equated to Harvard or Oxford for ceramics).

After teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design for four years, Archambeau and his family (which grew to include a son and daughter) moved north to the University of Manitoba in 1968. He stayed until retirement in 1993, but kept a studio as professor emeritus, alongside his studio in Bissett in eastern Manitoba.

He spent time in Japan, where he lived for a time, and South Korea.

“In Japan, ceramics is unquestionably a fine art. Here, it’s sort of a fine art with an asterisks on it saying, ‘well it’s really a craft’ — a difference in prestige from painting or sculpture. In Japan and Korea, where his work was well-received, they really see it as one of the central fine arts,” Robert says.

“He really liked Japanese esthetics, where things are plain and simple and perfect.”

Archambeau was awarded the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2003. In 2008, the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts gave him a lifetime achievement award for “extraordinary contribution.”

In 2014, he took home the Manitoba Arts Council’s Award of Distinction “for achieving the highest level of artistic excellence while building a monumental legacy in the field of ceramics on a provincial, national and international level.”

For Archambeau, however, it was about the work and the product and the appreciation, not the accolades. He would compare his work to the Japanese masters and think it came up short sometimes — while later, it wouldn’t, his son says.

“A big part of it was this ethos he had: it wasn’t about money, it wasn’t about fame, it was about doing work that you believed in. It took me a long time into my adult life to realize how much trouble that saves you as a human being,” says Robert, a poet and writer.

Archambeau was a quiet and studious type, who gently commanded respect.

“He wasn’t a loud person or anything like that, but he’d walk into a room and he had a certain kind of authority to him… It wasn’t like a disciplinarian, he was there to tell you what to do, but he was a substantial person.”

Archambeau travelled widely and collected fine arts and crafted goods, always reflecting what was available locally.

“Wherever we lived, whether it was in Manitoba or Maine or in his own travels, all over the place, he had this supernatural ability to walk into any kind of junk shop and walk out with something really amazing, like a 16th century Korean vase or a Turkish cavalry sabre,” his son says, noting it made it difficult to buy him presents.

“We would relate to each other via beautiful and rare handmade objects, which is what he found important in life.”

A celebration of Archambeau’s life and work is planned at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in the coming months.

passages@freepress.mb.ca

A Life's Story

February 21, 2026

‘There was nobody else like Kevin’

Career electrician loved cars, music and food

View MoreA Life's Story

February 14, 2026

Living, loving and laughing

Community leader took care of others as a nurse and devoted friend

View MoreA Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View More