A Life's Story

September 17, 2022

Above and beyond

After a lifetime providing for others, Joseph Ewanchuk’s generosity didn’t end with his death

By: Kevin Rollason

In life, Joseph Ewanchuk helped many people and, in death, he may help many more.

That’s because Ewanchuk, who was 93 when he died on Dec. 6, decided before his passing to delay having a funeral service and instead donate his body to science.

Joanne Marchand said the donation was just like her dad.

SUPPLIED

Joe Ewanchuk, who died on Dec. 6, 2021, donated his body to science.

“He thought about this 10 years ago or even further back — it was before his stroke,” Marchand said. “It was extremely important to him. ‘What good is my body after I am gone?’

“Dad believed in not just doing what is best for you, but also what can you do to help others.”

Dr. Sabine Hombach-Klonisch, head of the department of human anatomy and cell science at the Max Rady College of Medicine at the University of Manitoba, said as many as 25 Manitobans every year make a similar decision.

“We are very grateful to the people who donate their body to the program,” Hombach-Klonisch said.

“It is very important for the students and for the health services… when a student comes to us for the first time we really make them understand the honour of the donation.

“We tell them this is their first patient.”

Hombach-Klonisch said it isn’t just future doctors and surgeons who learn their skills through the donated bodies, but also nursing and pharmacy students.

“It provides them with a unique opportunity to learn with people,” she said.

“You can look at textbooks, look at MRI and CT scans, but this way you see an actual person. The learning is different when you have a real person instead of a plastic model.”

SUPPLIED

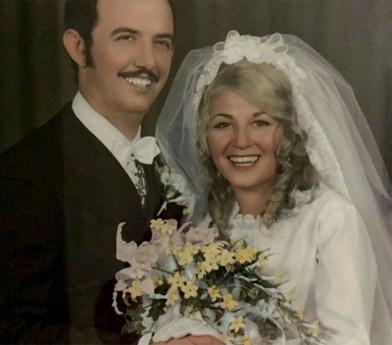

Joe Ewanchuk and his wife Louise did not stay married, but they stayed close friends.

SUPPLIED

Joe Ewanchuk with his wife Louise.

Hombach-Klonisch said the bodies stay with the program for a maximum of four years and then the ashes are interred in Brookside Cemetery or given back to the families.

“The students are invited and they even make speeches.”

Ewanchuk was born to William and Anna and went to school in St. Malo where, as his daughter said, he was with the “French kids” so he learned to read, write and speak French, something he was very proud of.

By the time Ewanchuk turned eight, he was hunting and helping provide for his family. Eight years later he was doing all the work on the farm.

He did well in school — he even skipped a couple of grades and had completed Grade 9 at age 13. But then he quit school.

“His cousin wanted to quit school,” Marchand said. “He loved school, but she struggled — he did it for her. But one of his biggest regrets was quitting school. He said he knew immediately it was a bad decision, but he was too embarrassed to admit it.

“He would always say to me, ‘Don’t ever be ashamed or embarrassed to change your mind and to say that isn’t what I want.’”

Perhaps that’s why he later moved an old schoolhouse onto the property and had it turned into the family’s home. It even came complete with the old school bell. “Dad would ring it for us to come for dinner.”

Inside the old school’s walls, Ewanchuk would read voraciously. He would read the Free Press from front to back, as well as books he picked up at used bookstores.

SUPPLIED

Ewanchuk worked until he suffered a stroke at age 84.

Ewanchuk worked from the time he quit school. Besides working on the family farm, he was a hired farm hand in Saskatchewan, and worked in the sugar beet fields, the railroad and in a mine. He was even promoted to be the cook at a bridge-building camp after working as a builder.

“He became the new cook when the original cook was fired after a night of drinking with the boss,” Marchand said, laughing. “The cook went to sleep on the top bunk and wet the bed. The boss slept on the bottom bunk.”

Ewanchuk later joined a roofing company, learning to become a tinsmith with eavestroughing. Five years later, when his boss wouldn’t give him time off to go moose hunting, he quit and started working for himself, installing eavestroughs and flashing.

Business was good. He worked on houses, but also churches, shopping malls, theatres, the original Sears building in Winnipeg, both the Dryden and Pine Falls paper mills, and the large silo grain elevators in Thunder Bay, Ont.

“Dad was a great employer who hired all of us kids — and probably every kid in St. Malo — to give him a hand from time to time,” Marchand said.

“You would help for 10 minutes and be paid $20. Everyone loved him.”

Ewanchuk finally stopped working when he suffered a stroke at 84.

Ewanchuk had two sons and a daughter with his wife Louise. They eventually divorced, but they remained close friends, even dancing the polka a couple of years before he died and making jam together annually.

Ewanchuk also provided for his family with his rifle. During his lifetime he shot 36 moose, and brought home six elk and somewhere between 200 and 300 deer.

SUPPLIED

Joseph Ewanchuk was a born outdoorsman and hunter who provided for his family from the land.

“We grew up eating wildlife, and a beef cheeseburger at a restaurant was a rare occasion,” Marchand said.

“We had almost nothing growing up, but if there was a way of helping somebody he would. He was the true outdoorsman. He was from a different era. He was a hunter and a trapper — he made sure everyone was well fed.”

Besides his family, Ewanchuk loved another lady — Pink Lady Slipper flowers.

“Dad took such great pride in keeping his rare wild orchids safe and then having his and his family’s efforts recognized when his property was officially acknowledged by the province of Manitoba as an ecologically significant area voluntarily protected by the land owner,” Marchand said.

“Every year, dad would spend two weeks carefully hiking individuals into the bush to see his beautiful flowers. This was after spending a week or two to make a safe path into the area so no plants were damaged by visitors. His biggest joy was showing off his flowers.

“Funny that once Dad got sick the flowers never bloomed as brightly.”

Ewanchuk had offers to buy his property, but he never sold. He was able to stay there until the day before he died thanks to one of his sons helping look after him.

“Dad loved living by the river and felt rewarded for his hard work in developing his farm,” Marchand said.

“Dad purchased the land from his grandmother who purchased it directly from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1926… dad felt a responsibility to the land for all it gave to us: it provided food for the family, drinking water, wood to heat the home, wildlife, fishing, orchids, relaxation, nature and the gift of sharing it with others.”

SUPPLIED

The orchids he grew on his property were Joe Ewanchuk’s pride and joy.

The earlier stroke not only left him with failing memory, it also started his battle with dementia.

“Although dad had no short-term memory, he still remembered us until the end,” Marchand said.

“After the stroke, if you asked dad how he was, his reply was always, ‘Same old way. Some days better than others and others just plain worse.’”

Besides his daughter, Ewanchuk is survived by two sons, two grandchildren, two sisters and one brother, and his former wife.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

A Life's Story

February 21, 2026

‘There was nobody else like Kevin’

Career electrician loved cars, music and food

View MoreA Life's Story

February 14, 2026

Living, loving and laughing

Community leader took care of others as a nurse and devoted friend

View MoreA Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View More