A Life's Story

September 06, 2025

‘He always looked forward’

Holocaust survivor overcame obstacles, lived a good life

By: Taylor Allen

It’s not easy to capture the undivided attention of a room full of secondary school students.

Isaac Gotfried’s story, however, would do just that.

Through resilience, creativity, and, most of all, luck, Gotfried survived the Holocaust. Born in Poland, he endured forced labour and concentration camps during World War II as a teenager. After the war, he and his brother Bernard — the only survivors from their family of seven — were sponsored by an aunt and moved to Winnipeg in 1947.

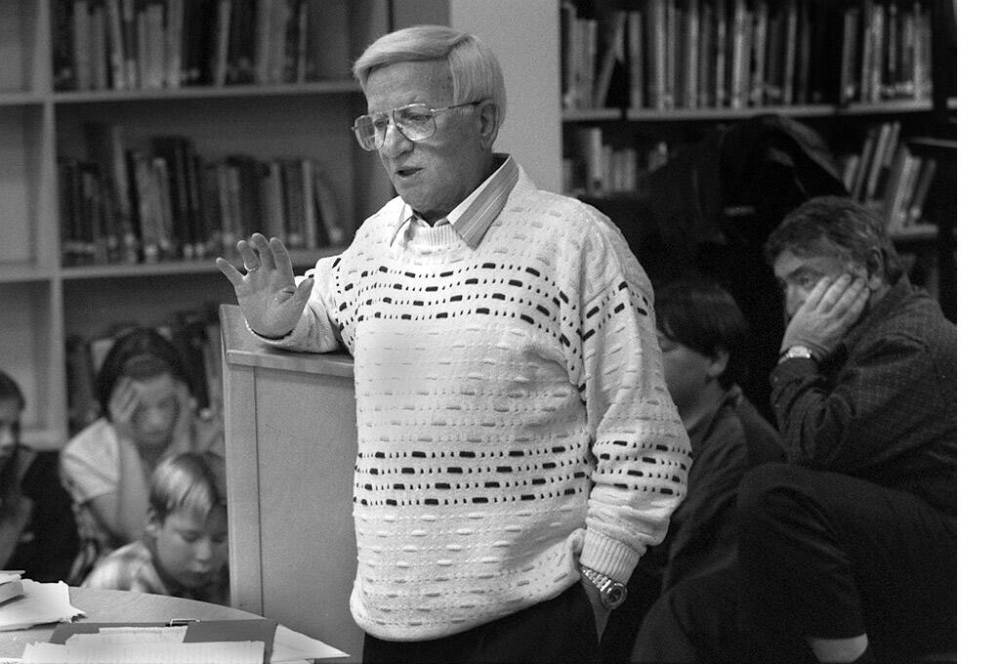

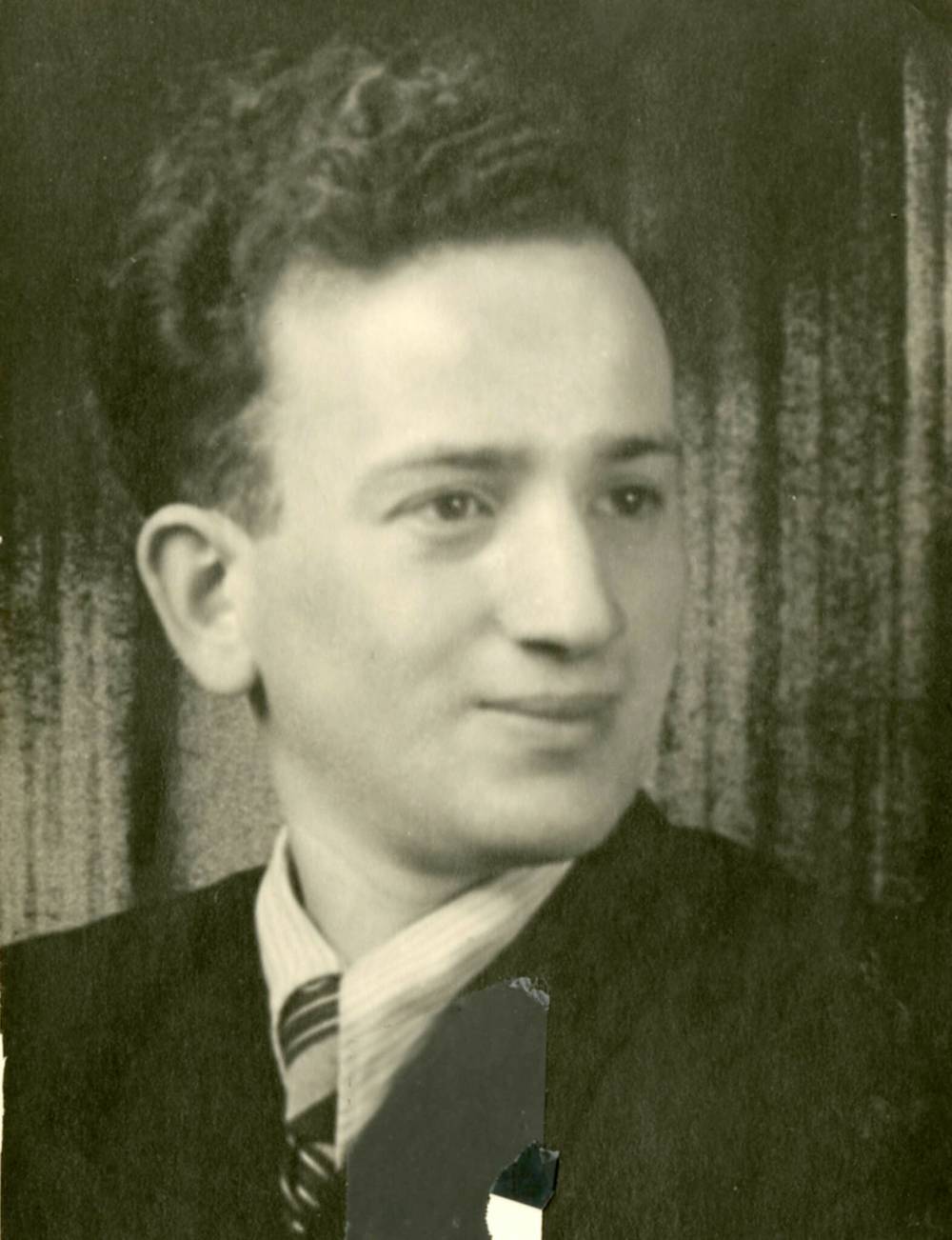

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS Files

Isaac Gotfried was 90 years old when he met with a group of students from Alberta participating in the Asper Foundation Human Rights and Holocaust Studies Program and visiting the CMHR.

Decades later, after retiring from a successful career as an insurance salesman, Gotfried devoted his time to speaking at schools across the province about the horrors he had faced.

“They’re rowdy, they’re noisy, they can’t sit still, they’re shoving each other and they don’t pay attention. And they’d be doing that until he started to talk and then there would be dead silence,” said Irene Shapira, one of Gotfried’s four daughters.

“These kids would be (sitting on the edge of their seats) the whole time and nobody moved. They were absolutely rapt and it’s a really tough audience, but they would sit there and eat up every word he said.”

The family estimates Gotfried spoke to over 25,000 people, not just at schools, but also at museums and conferences locally and internationally. His story was also documented by the Shoah Foundation, which was founded by legendary filmmaker Steven Spielberg in 1994, shortly after completing Schindler’s List.

For Gotfried, who spoke publicly well into his 90s, ensuring that the Holocaust would never be forgotten was a priority. As a thank-you for one of his talks, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) gifted him a small plaque that read, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Gotfried displayed it by the front door of his suite at the Shaftesbury Park Retirement Residence.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS Files

Gotfried was 90 years old when he met with a group of students from Alberta participating in the Asper Foundation Human Rights and Holocaust Studies Program and visiting the CMHR.

Gotfried passed away on Feb. 3, months shy of his 100th birthday. The plaque now hangs in the home of his granddaughter, Casey Challes.

“I wanted to also put it at my front door to show that it represents what our household believes in: that everyone is equal,” said Challes. “That’s really the lesson I took from my zaida. Even though he talked a lot about the Holocaust and Jewish people, he also emphasized that injustice shouldn’t happen to anyone.”

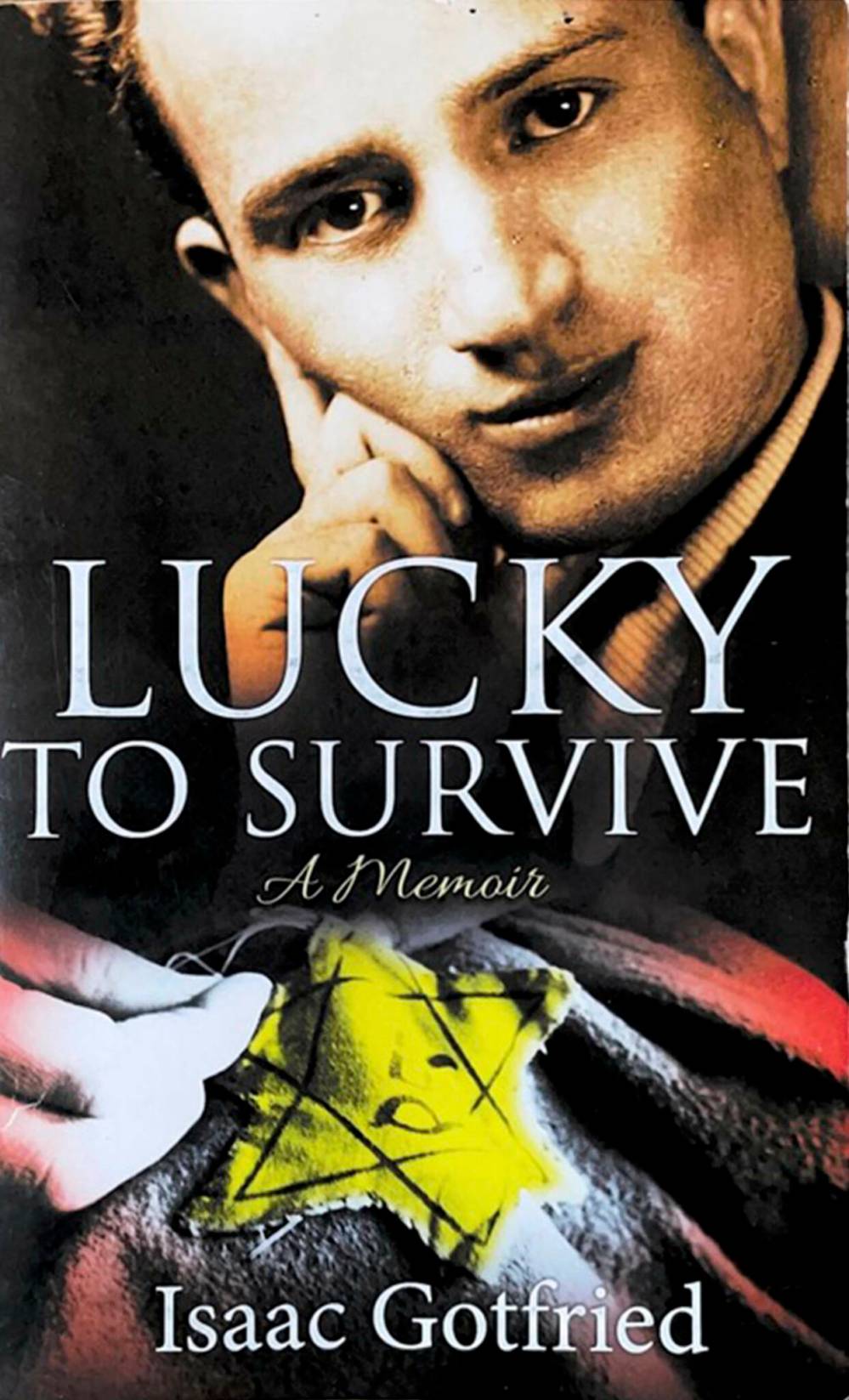

When Gotfried was 92, he published a memoir titled Lucky to Survive. Challes spent countless afternoons with him, typing up 118 pages of his memories.

The book is now found in most high schools and middle schools across Manitoba.

“He never intended to write a book. He had been writing his story by hand so his kids and grandchildren could have it,” said Shapira.

WAYNE GLOWACKI / Free Press Files

Gotfried was 71 when he spoke about the Holocaust to students at Nordale School in 1997. Over his long life, family estimates Gotfried spoke to more than 25,000 people, locally and internationally.

“Then we kind of encouraged him to actually organize it and get it printed. Then one after another, people who knew what he was doing would say ‘Well, could I get a copy?’ He wanted 10 copies made, and in the end, he agreed to 25 copies. We had a book launch and more than sold out as we sold over 100 and had to take orders.”

Challes added: “I was really lucky that I was the one that got to work on it with him. It was really important to me that it was his language and his words. He made the best sellers list at McNally Robinson which he was very proud of. He sold over 1,000 books in the end.”

He didn’t make a penny from the project. All proceeds went to the CMHR.

The title was fitting. Gotfried had countless near-death experiences throughout the war.

“He saw people dying around him all the time, either dying because their bodies gave out, or dying because they were beaten to death or shot to death,” said Shapira.

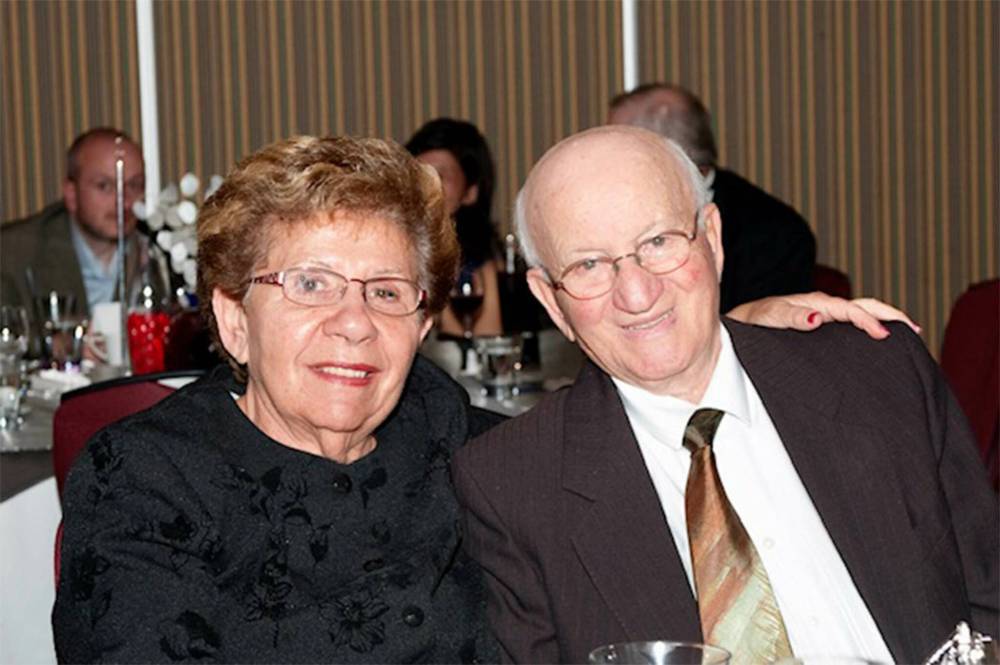

SUPPLIED

The Gotfried family: Isaac and Hilda with their daughters (from left) Susan, Irene, Paula and Marla.

At night, Gotfried and his fellow prisoners would cry themselves to sleep, starving and longing for their loved ones. Breakfast was nothing more than dark bread and imitation coffee. After 12 hours of grueling labour, they would be given a thin bowl of cabbage or beet soup. Sometimes, Gotfried would rummage through garbage bins, scraping green mould off old bread and cake just to get a little more to eat.

As the war neared its end, the Germans began organizing death marches, forcing prisoners to walk long distances to train stations where they would be transferred to new camps. By then, they were only given a slice of bread every two or three days.

“He said people would stop, lay on the ground and pull their hats over their heads, waiting to be shot because they were done,” said Challes.

On the first night of one such march, Gotfried and a large group of prisoners were housed in a barn full of straw. When it was time to leave the next morning, Gotfried buried himself in the straw, hoping the guards wouldn’t notice him missing. He planned to escape once the others left.

It turns out he wasn’t the only one with that idea. About 40-50 other men were also hiding in the straw. The guards began firing shots into the barn, and Gotfried heard the screams of those who had been hit. The men stayed hidden until the guards brought in barking German shepherd dogs. They lined everyone up against a wall, preparing to execute them, until one prisoner yelled “Let’s run!” in Polish. The guards didn’t understand Polish and were caught off guard by the mass escape. A few dozen men were chased down, caught, and shot.

SUPPLIED

Gotfried and Hilda were married for 68 years. After he retired, the couple spent winters in Palm Springs and summers at their trailer in Gimli.

Gotfried didn’t stop trying. One night, he walked into the forest to escape, pretending to collect dry branches for a bonfire only for a civilian farmer to spot him and return him to the guards. They roughed him up a bit, but to his surprise, did not shoot him.

“He was very small and looked young, so sometimes he could get away with things others couldn’t,” Shapira explained. Her father was only 5’2” and weighed just 80 pounds at the time.

“He always said he was lucky.”

On his third attempt, Gotfried succeeded. The march had stopped at an intersection and the guards were preoccupied trying to figure out which direction to go. Gotfried snuck away, crawled under a hay wagon, and pulled his pants down to appear as though he was relieving himself. When the march resumed, his absence went unnoticed and he waited for the right moment to flee into the forest, where he found an old German uniform. For a while, he was homeless and bouncing around from barn to barn before reuniting with Bernard and eventually finding their Canadian relatives.

Three years after arriving in Winnipeg, Gotfried met Hilda Goldberg, the love of his life. They were married for 68 years. Despite having only a Grade 6 education, Gotfried became an award-winning salesman for London Life. In retirement, he and Hilda enjoyed traveling, spending 15 winters in Palm Springs and summers at their trailer in Gimli. Hilda passed away in 2019.

SUPPLIED

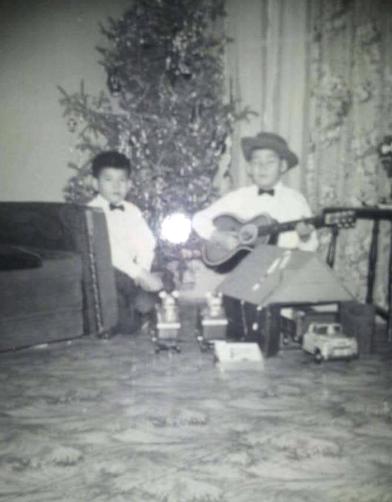

Gotfried shortly after arriving in Winnipeg in 1947. He was in several concentration camps from ages 15-18.

He was a family man, as he often said his children were his investment and his grandchildren — including three great-grandkids — were his dividends. He constantly read up on history and geography and had a passion for cracking jokes — often repeating the same material.

In 1999, Gotfried suffered a massive heart attack and underwent triple bypass surgery. Doctors predicted he had about 10 more years to live, but once again, he defied the odds and survived.

Through everything life threw at him, Gotfried found ways to persevere.

“What I learned most from him,” said Shapira, “is to live your life well, no matter how hard it’s been. He really had a good life after coming to Canada. He arrived with just $10 in his pocket and no knowledge of English, but he was proud of the life he built. He overcame so many obstacles, and he was never bitter or angry. He always looked forward.”

taylor.allen@freepress.mb.ca

A Life's Story

February 21, 2026

‘There was nobody else like Kevin’

Career electrician loved cars, music and food

View MoreA Life's Story

February 14, 2026

Living, loving and laughing

Community leader took care of others as a nurse and devoted friend

View MoreA Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View More