A Life's Story

April 19, 2025

Secret soup of kindness and character

Polish-born queen of the kitchen at Crossways in Common made Winnipeg her home, generosity her legacy

By: Ben Waldman

Every chef has their signature dish. For Julia Child, it was vichyssoise. For your grandmother, it might have been an earthy borscht with a dollop of sour cream. In West Broadway, Zyta Zepp was famous for her hangover soup, which always tasted different but was each time made the same.

Each Monday, a treasure chest of donated foodstuffs would arrive at the 1JustCity community kitchen at Crossways in Common, where at least 500 people lined up for free meals each week. She did not have the luxury of hand-picking her ingredients, so each hangover soup was stirred into existence by means of improvisation.

But that didn’t mean Zepp — who died last May at age 67 — made any excuses for absence of flavour. Spaghetti sauce, pearl barley, pickles and cheddar? It went in the soup. Basmati rice, chicken thighs, lemon juice and prunes? Zepp made it work. From her garden on Furby Street, she’d contribute her own fresh dill and onions when they were in season.

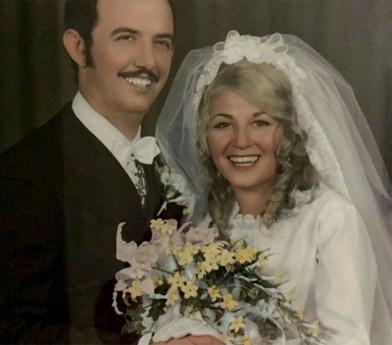

SUPPLIED

Zepp married Jim at the drop-in at Crossways in 2020. He still marvels at ‘the ability that she had to turn out something original, delicious and nutritious day after day.’

“I’m a pretty good cook, but I never had the ability that she had to turn out something original, delicious and nutritious day after day,” says Jim Zepp, who married Zyta in a ceremony at the Crossways drop-in in spring 2020.

“In line they’d ask what’s in the soup and she didn’t list the ingredients. Either she didn’t remember or she didn’t know the word.”

From her first shift, Zepp made the kitchen her domain, recalls retired United Church minister Lynda Trono, who hired “the boss” in 2012 after the centre received a one-time grant from the Westworth United Church for a hot-lunch program. After the six-month pilot period ended, a dozen churches from across the city stepped in to provide annual funding, which kept Zepp above the stove with a ladle for 12 years.

“In the food line, Zyta dealt with everyone as if they were her next-door neighbour,” says Jim Zepp. “The lady with three kids at home got an extra bag of sandwiches and it was done quietly with no fuss.”

Zyta Zepp (née Antoniewicz) was born and raised near Slubice, Poland, a few kilometres from the German border. The family ran a fairly large cattle farm, where Zyta’s interactions with animals inspired her to become a veterinarian’s apprentice before migrating to Canada in the early 1980s.

One of 11 siblings, Zepp, who stood five-foot-two, was a fraternal twin to a brother a full foot taller. That didn’t mean that Zyta let her brother, who became a police officer, tell her what to do. “She stole his squad car on more than one occasion and drove it into the bush,” her husband says.

In communist Poland, the independent and fiery Zepp was frustrated by the lack of opportunity afforded to women, while also contending with food scarcity and the ominous threat of martial law. Between 1980 and 1982, ahead of Poland’s social democratic revolution in 1989, Polish emigration to Canada increased by about 600 per cent.

As a major centre of Polish immigration at the turn of the 20th century, Winnipeg showcased significant support for the Polish solidarity movement and, as such, drew a considerable proportion of newcomers ahead of the country’s communist dissolution. Like hundreds of young families in Poland, Zepp and her first husband, whom she would leave a few years later, sought out a future in Manitoba.

The competition for immigration documents was stiff. “The pile on the officer’s desk was more than six inches tall,” says Jim Zepp, recalling the story as told by his wife.

But Zyta tipped the scales by stuffing her application envelope with hundreds of Zloty. “Magically, her file went from the bottom to the top. She got a phone call back in just a few days. ‘When can you leave?’ they asked. She told them, ‘Next week.’”

Supplied

‘Despite her sometimes gruff exterior, Zyta (Zepp) had a real soft heart,” says Commons’ Lynda Trono.

Zyta transferred her interest in the family farm and, with her husband and their infant son, arrived to Winnipeg in 1982. Soon after, Zyta was hired at a Jewish seniors home in the North End. She spoke no English and many of the residents favoured Yiddish, allowing for relatively fluid conversation. “That’s where she learned her English,” says Jim Zepp.

Shortly after starting at the community kitchen, Zepp — who also raised a daughter, Diane, and became a dedicated grandmother of four — was asked by a man in line for a serviette. She told him that she didn’t understand and he told her to go back to her own country.

“That was one of the only times her lack of English caused her any grief,” says Jim. “She had a wonderful accent that most people found pretty joyful. She didn’t always get the words right — she got 90 per cent right — but she was bound and determined to get through everything just the way she was.”

It was rare that the speaker of Ukrainian, Polish and Russian ever backed down. “One of the words was stubborn, the polite word was steadfast,” her husband says. “She spoke her mind, short and sweet. Well, maybe not always sweet, but kind.”

“Despite her sometimes gruff exterior, Zyta had a real soft heart,” Trono says. “She treated the most vulnerable with extra care. William, who was partially blind, had his coffee served to him. Herman, who shook like a leaf and couldn’t speak so well, would get his meal before anyone else. And for Alida, who struggled in here with her walker every morning to play cards, Zyta would serve up a side dish of early morning pickles with her coffee.”

Comedy writer Lara Rae, who volunteered with and technically worked above Zepp at 1JustCity, says her friend was free from the constraints of public expectation. A merry joker, Zepp’s humour was old-school, hard-edged and razor-sharp.

“Zyta said the most unrepeatable, horrifying things all day, but there also wasn’t a hateful bone in her body. In all the ways we understand the term in this day and age, Zyta was a survivor,” says Rae, who DJed the Zepps’ COVID-era wedding. “When I came into her kitchen, that was her domain, and even though I was effectively her boss, she made it clear that nobody but her was in charge and that was good for me.”

“The first time I met Zyta I knew how amazing she was. She took me under her wing,” says Anisha Saddler, a community drop-in leader who spent several years working with Zepp. “It was always dancing in the kitchen with the radio going.”

She and Jim were introduced by fresh produce.

Supplied

From her first shift at the West Broadway community space, Zyta Zepp made the kitchen her domain, recalls Lynda Trono, who hired ‘the boss’ in 2012.

“They used to do a farmers market here and I was volunteering with the Good Food Club,” recalls Jim. “She had a bag with 10 to 15 pounds of cucumbers. She comes walking up and asks to borrow some money. I lent her $40 and she spent every penny on cucumbers. But she realized she didn’t know where I lived. A week later she came back (to repay) and said it amazed her that I lent her money just because she needed it. After that, we had a bond between us.”

After years of friendship, the connection turned romantic. For their unofficial first date, Jim made Zyta homemade soup.

Two years before the pandemic, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and the disease went into remission. In 2022, her son, Mark, died. Last February, a CT scan revealed that she had an aggressive form of pancreatic cancer.

A few days earlier, the couple’s West Broadway apartment had caught fire, displacing all of the residents; the building still hasn’t welcomed tenants back, Jim says.

However, the pigeons his wife used to feed still return to the sidewalk out front, waiting to eat from her hand.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

A Life's Story

February 21, 2026

‘There was nobody else like Kevin’

Career electrician loved cars, music and food

View MoreA Life's Story

February 14, 2026

Living, loving and laughing

Community leader took care of others as a nurse and devoted friend

View MoreA Life's Story

January 17, 2026

Curious and fearless

Multi-talented mother embraced all opportunities

View More