A Life's Story

August 25, 2018

Feeding her family, feeding her soul

Nourished by her Ukrainian life in Canada, Holodomor survivor made sure no one went hungry.

Borscht, cabbage rolls, perogies, and honey cake for dessert if it was Ukrainian Christmas.

Those were the dishes on Maya Kirichenko’s menu, the platters she always prepared in ample amounts for holidays and wholesome family celebrations of all sorts.

Maya Kirichenko in Germany in the 1940s before immigrating to Winnipeg. (Supplied photo)

The mother of three, babunia of six and great-babunia of seven, never failed to make sure her loved ones were well-fed, and only then would she take a spoonful for herself.

A Holodomor survivor, food security was an unusual concept to the proud Ukrainian until she immigrated to Winnipeg as an adult.

"I think that’s why she respected food as much as she did — because she knew the value of it," her 35-year-old granddaughter Maryna Melnyk says.

Kirichenko was a humble woman who didn’t shy away from sharing her supper; she offered her plate to everyone, even those in the dining room at the retirement home where she died March 27 of a respiratory infection at age 91.

She was born on Oct. 25, 1926 to Mykhailo and Ephrosinia Solomenko in Sloviansk, a city in eastern Ukraine with a tumultuous history of German occupation and being the target of genocide.

She was one of five girls; the second-oldest of the bunch. She became the middle child when two of her four sisters died in the 1930s. The rest of the family was fortunate to survive starvation.

The Holodomor, a man-made famine imposed by Joseph Stalin, the dictator of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics at the time, occurred in 1932 and 1933. Disempowering Ukrainians was at the heart of Stalin’s policy decision to replace independent farming with state control. If Stalin could control food supply, he could control the population.

Maya and Volodymyr Kirichenko and two of their three children, Eugene and Nadia, at their home on Seymour Street. (Supplied photo)

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Kirichenko didn’t remember eating breakfast until she turned 15 because of the food shortage during the famine and its subsequent fallout.

"My mother had to stop going to school because she started fainting on the way," says Nadia Melnyk, one of Kirichenko’s daughters.

Kirichenko’s parents were worried about her health and sent her to live with her childless aunt — who could afford to feed her — for a few months; she was able to regain her strength and returned to class.

One of the eldest siblings — even at the young age of six — and willing, Kirichenko was counted on to find food for her family throughout her childhood (her father worked and her mother took care of the others). She would venture out on an empty stomach, often empty-handed, waiting in line for hours for rations of milk and bread. She once walked 65 kilometres to find somewhere she could barter food for clothing articles her mom had given her.

When her mother didn’t have anything to give her to trade, Kirichenko would walk parallel to train tracks in search of potatoes that had fallen out of boxcars. Or she snuck onto Nazi-owned farms in search of leftover oats covered in horse saliva in the dirt. She told such stories to the generations after her; she was never without a story to tell.

Kirichenko flippling pancakes at a Sunday school retreat. (Supplied photo)

In the fall of 1942, she said goodbye to her mother for the last time, unknowingly. In fact, the 15-year-old didn’t know much about what was to come at all, let alone why she’d been called to the train station. She was 15 and she was being shipped off to Germany as a slave labourer. (Despite her hard and rather unfair life, her grandson Tymon Melnyk said he never once heard her complain about anything.)

She would work in a factory producing bombs for the Nazis for nothing but slop; if she was really lucky she might get 100 grams of chocolate. Blue dust lingered in the factory air.

"It affected her health for her entire life, all the dust she breathed in. She had constant respiratory problems," her daughter Nadia said.

At some point on the job in the mid-1940s she met Volodymyr Kirichenko. "He was shy so he sent someone else to tell her he was interested in her. My father had red cheeks and so the fellow told her, ‘It’s the fellow with the red cheeks,’" Nadia said.

They were married shortly after they met and Kirichenko gave birth to her first child, a boy they named Eugene in 1948. Two years later, the family was sponsored by a farmer in Winnipeg. They immigrated to Winnipeg and raised their family of five in the North End, a place where they could finally embrace their Ukrainian heritage without fear. Her husband worked as an upholsterer and after she put the kids to bed, she cleaned offices.

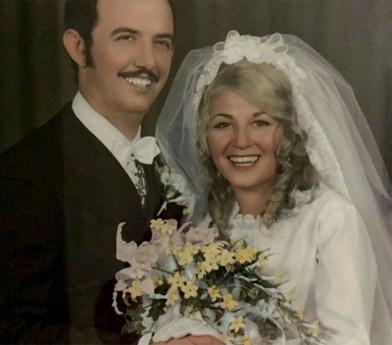

Maya and Volodymyr Kirichenko. (Supplied photo)

She became a widow after Volodymyr’s sudden death in 1997.

Pinching perogies was one of her favourite pastimes at the women’s club in St. Mary the Protectress Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral, where she would nurture both her stomach and deep faith. She was known for baking korovai — Ukrainian wedding bread — for new couples in the community and flipping pancakes at Sunday school breakfast.

Whether it was cheering on her grandchildren while they performed traditional dances at the Kyiv pavilion at Folklorama or introducing herself to strangers she overheard speaking Ukrainian at Safeway, Kirichenko embraced Winnipeg’s Ukrainian community. The family spoke Ukrainian at home, but Kirichenko read the Winnipeg Free Press every morning to improve her English reading, writing and speaking.

If she wasn’t at church, Kirichenko could be found gardening in her West Kildonan yard; her summer harvests included cucumbers, green onions and tomatoes. She also put her dainty hands to good use sewing clothing and costumes. If it was October, she was likely stitching a witch, pirate or princess costume for one of her grandchildren.

"She loved living in Canada and was very grateful for everything that Canada had given her family," Nadia says. Kirichenko returned to Ukraine to visit her hometown twice and paid for her sisters to visit Winnipeg.

Her family, both back in Ukraine and the relatives in Winnipeg, were of great importance to her. Even when she was feeling sick, she would always attend birthday dinners with hot food in hand. She vowed to keep those around her full since she knew what it was like to have an empty stomach.

Even when she died, Kirichenko’s family didn’t want her to be without food again. Since cereal was rare in her home growing up, they made sure to fill her casket with golden wheat.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

A Life's Story

December 13, 2025

Born to be wildly enthusiastic

Full-hearted family man, actor, photographer, teacher, motorcyclist lived life at full throttle

View MoreA Life's Story

December 06, 2025

A winning hand

Devoted matriarch made most of cards she was dealt

View MoreA Life's Story

November 29, 2025

She made life better for others

Accomplished artist, musician and entrepreneur who designed clothes for breast cancer patients always put others before herself

View More